NOTE: The following post discusses the impressions I got with the Xamarin.iOS framework alone. It was intended to discuss only the iOS development support and not the cross-platform capabilities of the Xamarin suite. It is also worth mentioning that Xamarin.iOS has nothing to do with Xamarin.Forms, a ver different beast focusing on cross-platform development, and a point of lots of online debating.

Yes, you heard it right. I tried Xamarin this weekend. I got an idea for a new app a few weeks ago, and I was interested to try something different. Plus, for those that have read my recent post about React Native, I am always on the hunt for ways to avoid Apple’s prescribed choice of language or tooling, so Xamarin seemed like a nice opportunity to do so.

SIDENOTE: There is no such thing like avoiding Apple’s tech or tooling, but one can abstract it away as much as possible, in the name a better and faster developer experience.

Basic Info

Xamarin dates back to 2011, originally developed by @migueldeicaza and his team, who also brought Mono, Mono for Android and MonoTouch to the world, and was later bought by Microsoft in 2016. Currently, Xamarin gets shipped together with every version of Visual Studio, including the VS Community Edition, allowing individuals or small non-enterprise teams to create mobile apps and distribute across the app stores, free of charge.

What is the big deal?

In short, Xamarin facilitates the development of cross-platform applications using a shared code base, while utilizing the best of the C# language and the .NET ecosystem. I will leave the cross-platform topic since it does not concern me for now, but from what I have seen, it seems to allow for a good deal of code sharing.

Source: Microsoft

As for iOS, Xamarin actually impressed me from the get go. It is hard to believe it for someone who has not tried Xamarin, but developing an iOS app does not differ much syntactically from using Swift. On top, one gets to use C#, a very mature and elegant language, albeit somewhat restricted by the platform availability that the .NET framework gets to run on.

SIDENOTE: During and shortly after my Undergraduate years about a decade ago, I spent a significant part of my programming practice writing C# and working with the .NET. My opinion can thus be a little bit biased, due to my nostalgia of that time.

A Xamarin developer has the entire CocoaTouch SDK at their disposal, plus a fairly good deal of the .NET framework. Bringing-in new .NET libraries is a piece of cake, and as long as they don’t rely on any platform or OS-specific SDKs, they work out of the box. Bridging to 3rd-party Objective-C libraries is also not a problem. There is a tool made available from Microsoft, called Objective Sharipie, which facilitates the bridging, by parsing Objective-C headers and creating a C# bridge. Bridging to Swift libraries is not officially supported for various reasons, but also not impossible. There are a few caveats to keep in mind before bridging a Swift library, so I can’t be 100% certain that the bridging effort will be always worth it. It’s … just there for those who are ready to spend some effort and take advantage of it.

Tooling

Visual Studio

The last time I really used VS (not to be mistaken with VSCode), was around 2010. Even back then, VS was a very good developer environment, but tightly bound to the Windows OS and its platform ecosystem. In that regard, VS back then as pretty much the Windows equivalent of XCode was at the time, … and still is 🤔.

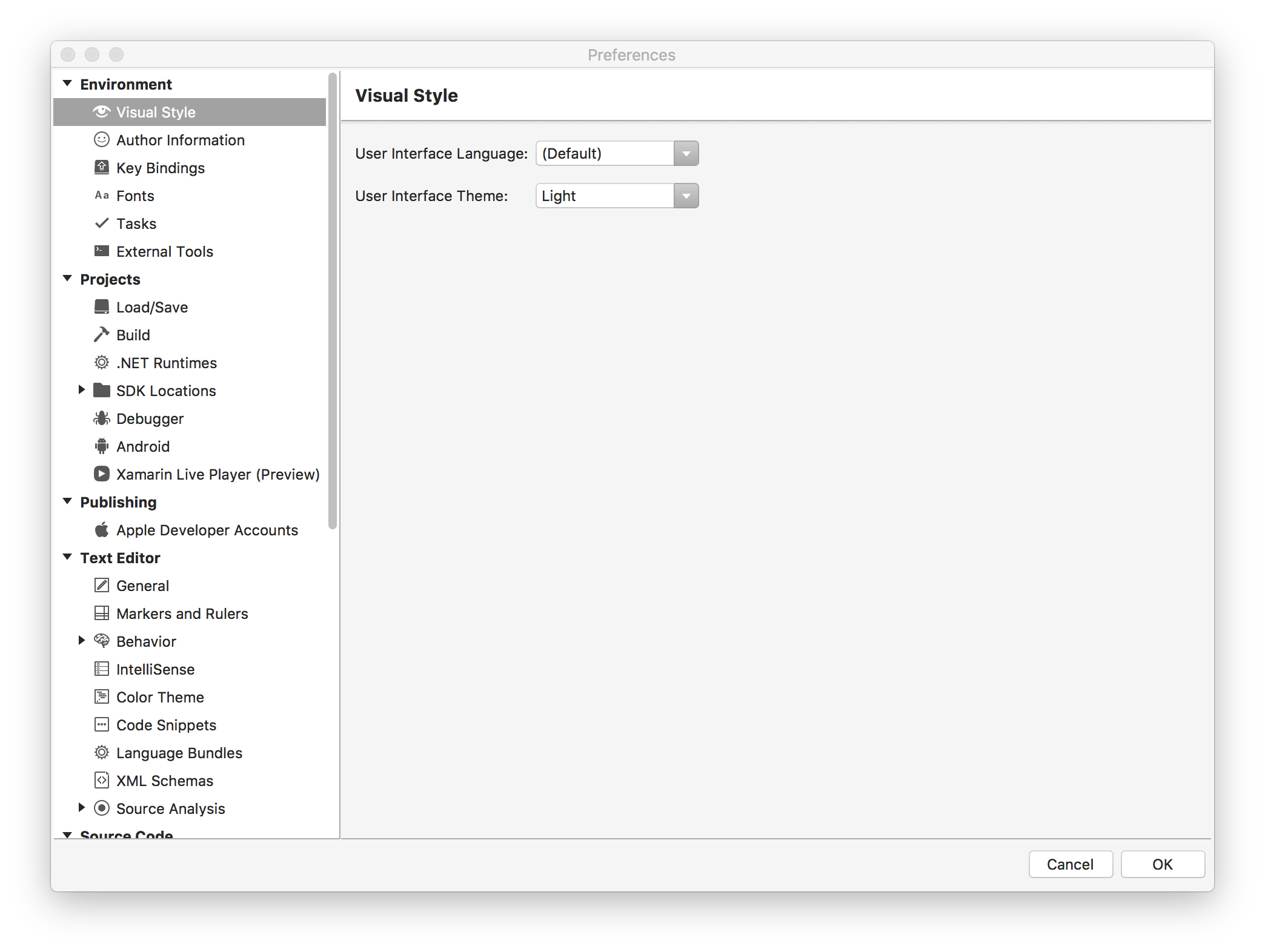

A lot has changed since then and in a very positive direction. VS follows along Microsoft’s core strategic pivot and rekindled love for developers of all kinds, and this can be seen right from the opening screen. I had very few issues installing VS on my Mac (On a Mac!!!) and right after setting up a demo iOS project, I set out to change my preferences. I was pleasantly surprised by the fact that the very first screen let me choose a dark UI. Not just a dark colour scheme. A full-scale dark UI.

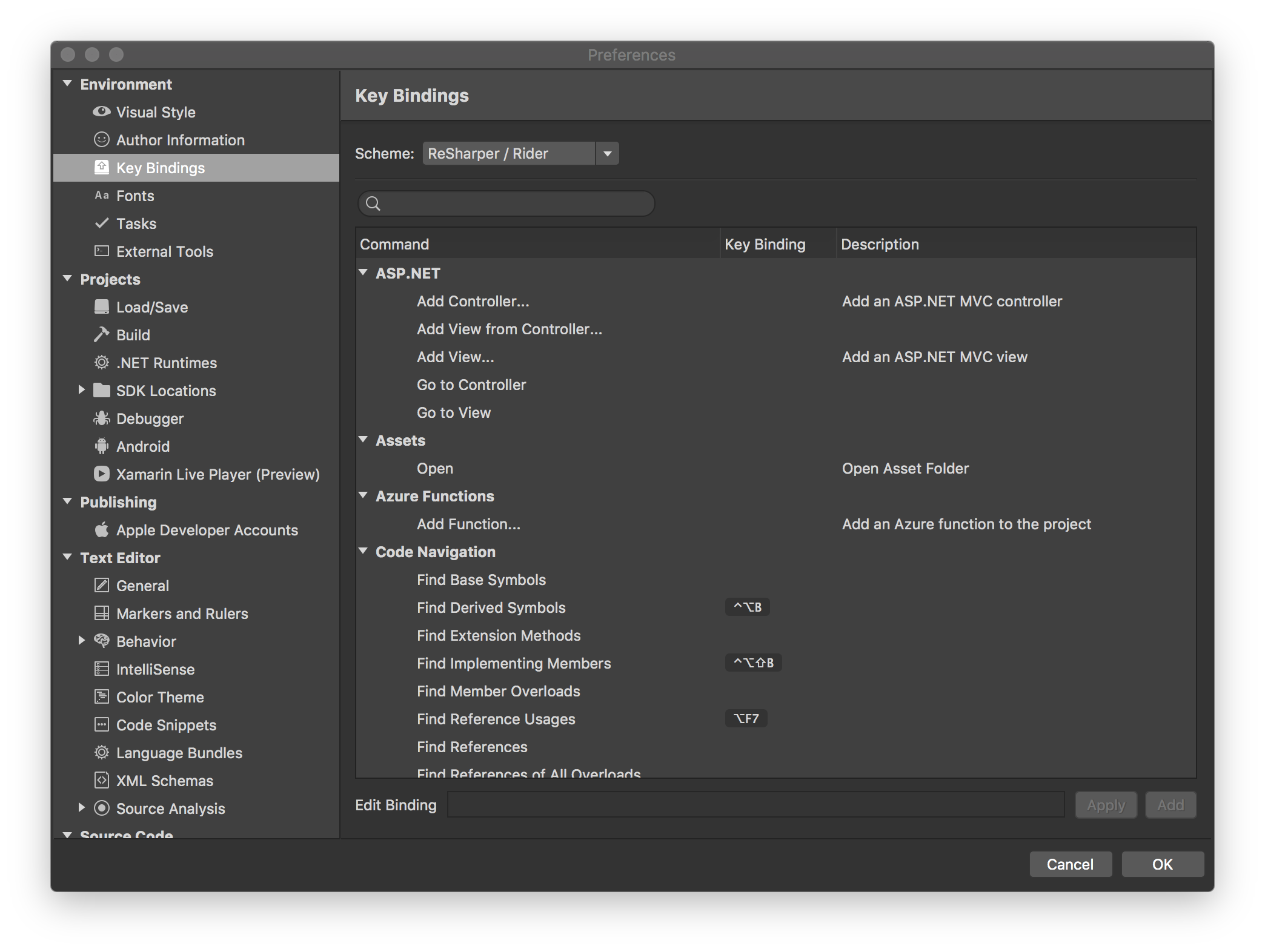

Next step, change the key shortcuts to something matching my IntelliJ workflow. Here too, I was positively surprised that Microsoft provided a key mapping coming straight out of Rider (JetBrains’ .NET IDE), which brought most of my favourite key mappings right away.

Unfortunately, not all mappings were provided, due to the fact that VS simply does not expose all the functionality available for key-mapping. As of yet, my two biggest issues are the inability to ditch tabs, and use a sorted “recently opened files” panel instead.

In case I decide to continue on the Xamarin path, I would definitely give Rider a try. I have heard many good things about it, and its seamless integration with .NET and Xamarin. Indeed, it’s a paid product, but I paid for AppCode and was utterly disappointed by it, so I think that there might be bit of room in the budget for the upcoming year.

The integrated iOS UI designer

The built-in UI designer is definitely not as bad as what I have been hearing from others. It reminds me of Xcode’s Interface Builder and is not any better or worse (I believe that it is actually using IB under the hood). For those who can’t part from their beloved Interface Builder, the storyboard file export format is exactly the same, so one can open the files in Xcode and do the necessary tweaks there instead. I am not so much of a fan of IB, and would rather often prefer to manage my views in code, so please, don’t rely on my opinion alone.

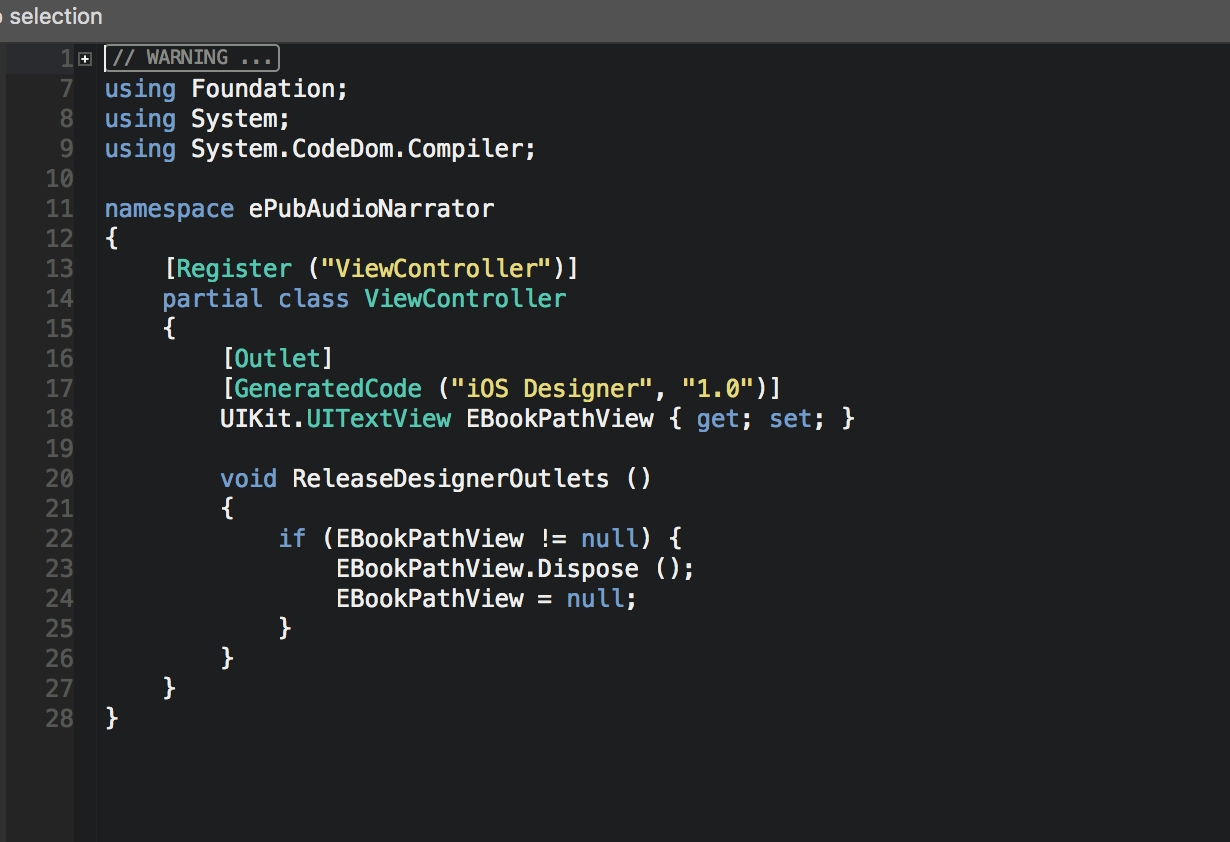

One interesting fact is that code references to views laid out using the UI designer, get autogenerated in code, and conveniently placed in a C# partial class right under the main view controller, essentially separating the UI logic from the instantiation of the view. I found this neat.

The Debugger

Unlike what I’ve heard or read previously, the debugger was also on par with everything I had expected. I haven’t had much time form some more thorough runtime introspection and profiling, so I can’t really comment on those features, but I believe that they should be on par with the rest.

Build Time

The build time seems fast or even faster than building the same app using Swift. During my test runs, I did not hear the fan of my laptop start even once. This is certainly not the case when compiling Swift code. One thing to remember is that the Xamarin code generator is essentially compiling the managed .NET intermediate language (IL) into a set of native instructions, using a process called Ahead of Time Compilation (AOT), which has some certain limitations. Also, in order to speed compilation time, the generator will not use the LLVM optimising compiler. By default, LLVM optimisation and other heavy-duty preprocessing steps (stripping unused parts of the code) are reserved for when issuing an actual release build. One needs to keep those in mind, and not merely discard Xamarin just solely based on the size or performance of a simulator test build.

What I Wish Were Better

The Documentation

A lot of stuff seems scrambled around. There are many good pages on the Microsoft site, which I tried to link to, but much of the information is still spread around. I found some of the juicy under-the-hood parts only by stumbling upon the original Mono Project website. Others I found after some digging around StackOverflow or in developers’ blogs, but from a very brief point of interaction, I seem to be missing a strong developer community which to turn to, in case one needs an answer.

I spotted a lot of false accusations online targeting Xamarin.Forms, or Xamarin’s capabilities at cross-platform development. There were, in fact, very posts that targeted Xamarin.iOS in particular, which would start right away with the negative stuff. My assumption is that people, just as it is the case with React Native, wrongly approach a framework like Xamarin, thinking that it will allow them to build cross-platform applications with native look and feel on each platform, and 99.99% shared code. I am sorry to unveil the mystery, but nothing like that exists on the market, or will ever exist for that matter.

Besides the documentation and the available information online, I think that the one of the biggest issues around Xamarin seems to be the Microsoft stigma around it. Somehow, if a framework were developed by, say, Google or Facebook, everyone would cheerfully jump on it in no time, but see, Microsoft is a whole other story.

Conclusion

I have decided, for the time being, to give Xamarin.iOS a chance. This does not mean that I would stop searching for new ways to undercut Apple. Let’s call it a bit of nostalgia of the old days, and partially, giving Microsoft the benefit of the doubt. C# as a language, and .NET as a toolkit are a mighty part, and I believe that people should give them a chance, before throwing the option right was as just another Microsoft product, whose legacy would chase you forever (as if Apple’s or Google’s don’t).

Leave a comment