Dominik Wagner (a.k.a. @monkeydom) published an article a few days ago, called On my misalignment with Apple’s love affair with Swift.

I fully respect Dominik’s opinion, and have read most of his blog rants with pleasure. I also don’t claim to be worthy of calling myself an iOS developer, despite my recent work on iOS, and my early exposure to Objective-C back in 2010, when ARC was not yet a thing. This post is my response from the point of view of a future-looking full-stack developer. Of someone who has seen projects fail out of technical debt, and others leapfrog because of doubling-down on something new and untried.

As a full-stack developer, I believe that choosing Swift was a deliberate decision towards a future, in which Apple’s product line of today might no longer be the main source of revenue for the company. It is about accepting the fact that developing quality and scalable software can only be achieved by embracing the developer community drive, and guiding alongside, rather than blindly dictating the way forward.

See, there is nothing particularly wrong with Objective-C as a language. It has done a pretty good job within NeXT and later, within Apple. But it is a rather opinionated abstraction on top of C - a language which, despite being the root of most of modern programming, comes with its own bag of design limits and shortcomings. The languages of the early era were designed to cope primarily with the limitations of the existing hardware at the time. The focus was not on how to make code reusable, but primarily, to make it do something, anything, at all.

When the iPhone was first introduced in 2007, the choice of a software development stack for Apple was more than obvious. With the strict hardware requirements at the time, it was a no-brainer that running as close to the metal as possible, using a tried and proven technology was the single way to go. Plus, recall that the original idea did not envision 3rd parties developing apps for the iPhone. At least, not in the scale in which they did, eventually.

So, from early on, Apple set the rules of the game, a benevolent take-it-or-leave-it ultimatum of sorts. The appeal of the company’s brand, the coolness factor of being an iPhone pioneer, and even the slight obscurity of the technology stack, attracted a lot of people, for many of whom, Objective-C and Cocoa Touch were the first real taste of programming.

When you are at the beginning of your programming career, working with a closed-source technology stack, focusing solely on bringing a product to market, it is easy to slip into following Apple’s guidelines and conventions, without asking yourself how stuff works under the hood, or how it could potentially be changed for the better. Even if those principles did not always seem like the best decision one could take, hey those come from Apple. It’s their platform, right? Apple can’t be wrong, right? Right?

I thought pretty much the same about Microsoft, back in 2006. Fresh into University, I joined a CS program funded by Microsoft, and therefore, heavily influenced by its tech stack at the time. I thought that C# and .NET, along with MS’ design patterns and practices, heavily focusing on building uniformly looking, closed source enterprise apps, were the only things one needed to know for a successful career. I tried to stay away from activities that involved the command line, or anything that needed more effort than customising a few drag-and-drop controls inside Visual Studio. Boy, was I wrong, and what’s more important, was Microsoft.

Time to embrace the change

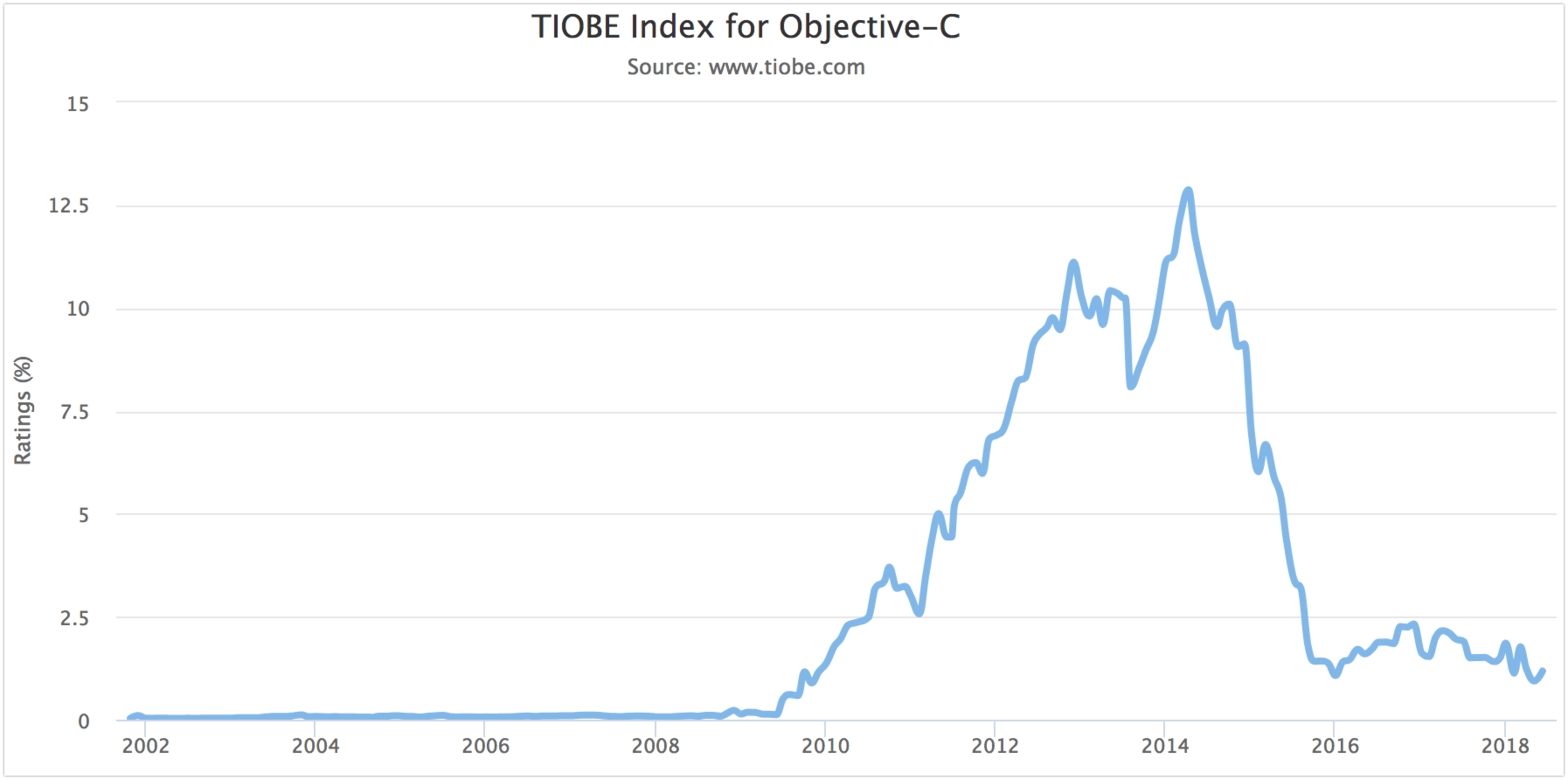

Like Microsoft, eventually, the time came for Apple to embrace the change too. A change, that would not have been necessary, were it not for the iPhone. Although Objective-C had existed for two decades before the iPhone, it was really the advent the device that brought the language to the masses, and not vice versa:

source: TIOBE Index

source: TIOBE Index

A language designed during the 80s with the sole purpose of making C a little more humane, and with a decade-old stack of proprietary libraries built with it, suddenly became the tool of hundreds of thousands of developers around the world. A set of design and development practices focused around building appealing and usable applications, but not necessarily reusable, scalable and robust architectures. Apple could continue to impose it on developers, but as the complexity of app use cases grows, it would have become harder and harder for the company to keep up with the constant demand for new features. A change was was supposed to happen, sooner or later.

Sometimes, a restart is inevitable, and the only way to look at the future. Restarts are often hard and transitions are long, but ultimately they are for the better of everyone involved. I understand most seasoned developers’ frustrations with Swift. It is by far not an easy language. Definitely, not the easy-to-learn language that Apple wants you to believe it is. At least, not yet. There is a lack of consensus in Swift’s evolution which is often letting it stray off the beaten path, and leads to additional complexity for both the developers and the compiler. Last but not least, the impedance mismatch between the language and the Cocoa/CocoaTouch stack adds yet an additional complexity on both the programmer and the compiler.

I can feel the pain, but I can also see a light at the end of the tunnel, leading to a bright future. A community driving force of Swift passionate developers which speak to one another, don’t fear to ask questions or tinker under the hood, and don’t hesitate to use every opportunity to teach, mentor, or share best practices. Developers from different developer backgrounds joining the Swift community and contributing their experience in turn. People taking a critical look at Apple’s patterns and practices, the unbreakable status quo. People sharing, and designing code with the intention to be shared, be it across mobile, on the server, on embedded devices, etc. People opening up to the change, going beyond the boundaries of mobile development, and embracing the unknown.

This vision of Apple’s future I want to live in. What about you?

Leave a comment